When I first moved to the UK at the age of 21, one of the things that struck me most wasn’t the weather, or the peculiarities of British small talk, but a comment someone made about me sounding “too direct” or “cold”, like “most Eastern Europeans”, supposedly. It wasn’t that I meant to sound cold—I was just speaking normally, or so I thought. But apparently, to native English speakers, my words felt flat, too direct, lacking warmth – “but that’s okay, Russians sound like this too, you just come from a colder culture“. It wasn’t just surprising—it was unsettling. I had always thought of myself as a deeply affective, sometimes overwhelmingly so: I cry at films, I feel rage rise like wildfire in my belly, and when I’m happy, I feel it spills out of me in a way I can’t contain. So to hear someone say I sounded cold and that it’s due to the cold culture was disorienting, like they were talking about someone else. But then I realized there was something deeper at play, something about the subtle interplay of valence with languages.

The Slavic diminutives are to blame – or to praise

I remember it dawning on me when I was thinking about something seemingly unrelated, about what I missed most about speaking Polish. It wasn’t just the comfort of my mother tongue – it was the diminutives that I always missed most. Diminutives are not unique to Polish; languages like Spanish have them too – add “-ito” to the noun to make it sound smaller or more endearing. But they are absolutely grown out of control in Slavic languages, and they are not just to “make a noun sound cuter” – they are a whole new realm of expression, they are nuanced, textured, rich with very subtle emotional undertones.

Take the word “cat”, for example. In English, a cat is simply a cat. If you want to express affection for it, you have to either say it explicitly—”I love that cat”— “The cat is adorable” – or infuse your voice with warmth. In Polish, you don’t need to say anything too extra – the word itself will change its shape to accommodate how you feel about it, no need to be too overt.

A simple, neutral Polish word for cat, kot. The simple word kot can morph into countless forms, each tied to a different feeling. If I call the cat, kociątko, you can feel how small and delicate the creature is, something that carries somewhat “protective feelings” with it. Kocik, on the other hand, brings a playful spark, for a cheeky little rascal that you still can’t help but adore. And then there’s kotunio, a soft, warm version of the word, suggesting that I want to cuddle it, that there’s a deep affection and coziness there. Kocinka—that makes me think of a cat that’s been through something, a cat that needs nurturing. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. There are even stranger, more whimsical ones, you can really be creative with it: kocuras, kocuszek, kocuch, kicior? Good luck translating those – I can’t fully pin them down myself. But when I hear kocuras, for instance, I picture a scrappy, battle-worn cat, perhaps missing a tooth, with a tough exterior that hints at a life well-lived. There’s a bit of roughness in the sound of it, but there’s also some affection and fondness smuggled in.

In Polish, I can gently mold a noun into something that reflects how I feel about it. It’s not just that we say different words to label external objects. Nouns are not necessarily neutral, standalone things in Polish; they shift with the tides of emotion, seamlessly integrated into how we perceive whatever they refer to. This fluidity is something I miss when speaking English. It feels like a loss—like I’ve been stripped of a natural apparatus to express myself.

When I operate in English, I’m forced to rely on intonation or explicitly state (over-explain) what I feel, on gestures that feel foreign, stiff to me (and somewhat overdone, now that I live in the US, where everything is so “aggressively amazing”). If I want to show affection, I have to make it clear, because English nouns don’t carry the same affective undertones. I must state my feelings, rather than letting them ripple quietly through the words I speak.

This linguistic difference doesn’t just affect how others perceive me; it also changes how I experience the world. When I speak Polish, my phenomenology of the world shifts slightly, the world feels more fluid, more connected to me. A cat is not just a cat; it really is a kociątko or a kocik or a kotunio, and I feel those distinctions deeply, each one carrying its own emotional weight, its own texture of meaning. In Polish, the boundaries between me and the world are softer, more porous, I bring the warmth of my inner life into the objects; In English, the boundaries harden, and I feel as though I’ve lost that connection, everything feels more separate. My feelings sit inside me, while the nouns stand outside, it’s as if the language erects walls where there should be windows.

I remember once trying to explain this to an English friend, and their confusion was palpable. “Why so many words for ‘cat’? Isn’t it all redundant?” they asked. I struggled to put it into words. How do you articulate something so instinctive, something so ingrained, so natural, in a language that doesn’t have the same flexibility?

If Eastern Europeans sometimes sound cold in English, it’s not because we are cold. It’s because we’re missing the subtle, intricate tools our native languages give us. We’re navigating the world with a blunt instrument where we’re used to fine-tuned precision (or if that sounds like a “typical Eastern-European arrogance” – we just never learn to rely on intonation that much, because we can rely on diminutives). And maybe that’s why we come across as too direct or detached—we’re just not immediately able to wrap our emotions around our words in the way we naturally would.

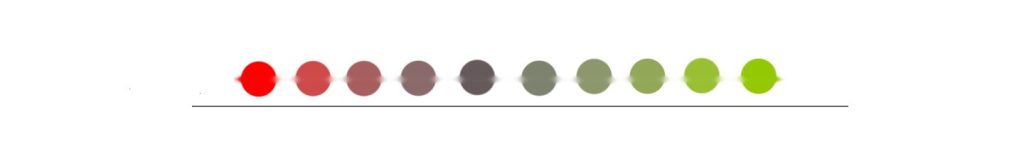

Now, what does all this have to do with valence?

Valence—the emotional texture of experience—exists independently of language. Evolutionarily speaking, valence is ancient, a primal force that likely predates our ability to communicate through words. It doesn’t need language. But language can expose something interesting about valence, it mediates how valence interfaces with the world, how our emotional tones cling to or slip away from objects.

While in Slavic languages, the boundaries between emotions and objects feel softer, more fluid, in English a noun stands for an object with neutral contours, the emotional resonance must be layered on top, not woven into the thing itself. In that sense, English forces a separation—my emotions remain inside me, while the object I am describing stands apart. It’s not that I feel less, but the feeling is less bound to the object. There’s a certain distance. The experience of valence becomes slightly less about the world and more about what’s happening inside.

This subtle distinction between languages isn’t trivial. It could be one reason why some cultures are more prone to falling into a direct realist view of valence. Direct realism is the belief that we perceive the world exactly as it is. Few people today, if any, are direct realists about perception, about the external world. No one argues that the color red is an inherent property of an object—it’s something created by the brain, even if it’s consistently triggered by a certain wavelength of light. Donald Hoffman’s Interface Theory of Perception takes this further, suggesting that even space and time are not direct features of reality but part of our mental interface.

Yet even if we aren’t direct realists about perception, most people are indeed direct realists about valence throughout their lives, often without realizing it. To be a direct realist about valence means believing that your happiness or pain comes solely from external triggers: get that delicious meal again, revisit that exciting place, avoid that painful conversation —acting as if pleasure and pain are true attributes of things, places, situations, rather than originating from within.

It makes perfect sense why valence is implemented in this sneaky way, why it evolved to stay hidden – to survive, you must be quickly compelled to act and feel certain ways about things that can help you or harm you, it would be counterproductive and potentially putting you at risk if there was too much space left for some stoic introspection. But today, when we do not need to worry about survival so much, it is empowering to see through the interface.

Once you realize that valence is something you generate, it opens the door to an incredible sense of freedom. You are the true origin of your emotional experience, not the objects or situations around you. You can, to some extent, escape the interface. And with this realization comes the opportunity to explore how your language itself might make it easier or harder to see through this illusion, how the way your nouns are structured are more or less invaded by your valence.

At times, I miss the effortless way Polish allows my emotions to blend with the world around me, as if my inner life could flow freely into everything I describe. But in English, I’ve come to appreciate a certain sharpness—its clarity carves out a space, and in that space, I can see a new kind of freedom. A freedom to see that I’m the one shaping the emotional landscape I move through, that I have more control over it than I often realize. The world doesn’t give me its valence—I give mine to it, and I can decide how much or how little to let it in.

Leave a comment